(Note: Many of the Wikipedia links in this article are from the German, rather than the English, version of the page, as they often have more information than the English version. If, like me, you don't speak fluent German, you can get around this by using the translate option of your browser in settings to easily convert them.)

Family Line Links: (WikiTree.com)(Ancestry.com)(FamilySearch.org)

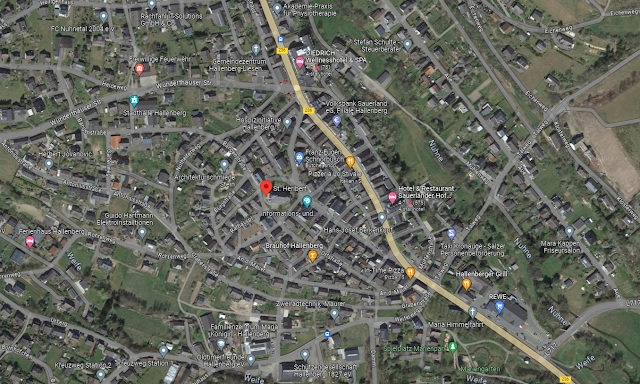

After doing some research on Dad's Wahle line recently, I was amazed to discover that we can now trace it back to Germany in about 1630, to a man named none other than Christopher Wahle! (Also my Dad's name for those not in the know.) In 1656, he is said to have married a woman named Rachel Lodderhose in the German town of Hallenberg, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany (though back then it was considered part of the Dutchy of Westphalia in the Electorate of Cologne in the Holy Roman Empire). It is only about 5 miles from the town of Züschen, where Dad's Schauerte line is from. Both are found in Central Western Germany, at the southeastern state border with Hesse. Hallenberg lies in the foothills of the Rothaar Mountains, part of the Sauerland Region, which is the most heavily touristed area of North Rhine-Westphalia today. It was built in about 1260 AD, and its enclosed mountainous surroundings allowed it to served as an important military choke point on trade routes between the nearby kingdoms of Arnsberg, Hesse, Wittgenstein, and Waldeck. It's original land owner was an archbishop from the town of Medebach.

States of Modern Germany showing the city of Hallenberg within North Rhine-Westphalia

Unfortunately, we don't know much more about Christopher Wahle (b. 1630) than that yet, and I haven't yet found a good record to confirm him. The

surname itself is supposed to mean "elector", and originates from the northern city of

Oldenburg, Lower Saxony, Germany, in about the 13th century. Most likely, someone in the family was part of the electorate who helped to select the Holy Roman Emperor. The first good record I have found is for the son of Christopher,

Otto Wahle (b. about 1660), who married Sybilla Gruesemann in Hallenberg in 1696. Sadly, it is unlikely that many older records will ever be found given the situation in Germany (ie Prussia) during that time period.

Hallenberg, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

Historical Background

The 16th-17th centuries in many parts of what is now Germany were pretty rough, due to a combination of the

Protestant Reformation, the Bubonic Plague (ie

Black Death), and good old

feudal village plundering. The Holy Roman Empire had held the authoritative power of the

Roman Catholic Church over the mainly

Saxon people of Germany since 962 AD. But it was now being challenged by the growing religious and social ideals of

Protestantism that had been put forth by

Martin Luther in 1517. One of the main differences between these two theologies was the Protestant belief that forgiveness of sins could be a private spiritual matter, between an individual and God, rather than a formal matter requiring the intermediary of a Catholic priest and the

Sacrament of Penance. The political and social implications of such a belief had huge repercussions during a time when church was not yet considered

separate from state. Rather, the authority of the Catholic church to rule the people was assumed to be a Divine Right. What, then, did it mean if even common peasants now had the right to petition God directly for their concerns, and be worthy of His answer? And what right did the church have to assert authority over this personal spiritual relationship?

grants the penitent absolution of sins

Understandably, the Catholic Church was very concerned about this questioning of its Divine authority over its people. But many in both the peasant and

lower noble classes were inspired by Martin Luther's teaching none the less. One way or another, a change in people's way of thinking about themselves in relation to God and authority had begun. In the 1500s, Germany was not a country, but rather a part of the Holy Roman empire, which was itself a collection of about 300 different kingdoms. This large number was due to differences in royal succession customs compared to many other areas of the world. Rather than the title of King being passed on to only the eldest son, the land was instead divided, and the title of Prince was

passed on to all the sons, thus splitting the kingdom into smaller (and weaker) parts as time went on. To overcome this weakening, the kingdoms also formed various Electorates, which were shifting collections of kingdoms (ie

Electorate of the Palatinate,

Electorate of Cologne, etc.) which acted together on matters of trade and security. Some of these Electorates were Roman Catholic in power origin, while others were more

secular.

Various Kingdoms of the Holy Roman Empire in 1356 due to early succession laws

The Electorates of future Germany varied in their openness to the adoption of the new Protestant ideas. Many areas of the north and east saw widespread conversion. The

law at that time was that whatever religion the prince-elector of a kingdom chose to adopt, it automatically became the only allowed religion for its citizens as well. At times this caused kingdoms to convert to Protestantism, only to reconvert back to Catholicism sometime later, which must have been somewhat confusing for its people. This happened in Hallenberg

in the 1580's. Over time, these shifting alliances caused power struggles both within and between Electorates, which broke out into religious wars.

Artistic depiction of the generations of conflict brought about by the posting of Martin Luther's 95 Theses on the doors of the church in 1517

Hallenberg, in Westphalia (ie Westfalen), was (and is) strongly Roman Catholic, but was relatively protected during the first 50 years of these conflicts, due to the majority of battles taking place in other parts of the region. However, movements of troops between areas of battle often resulted in villages along the way being ruthlessly raided for food and supplies. Additionally, traveling troops often brought new variants of the Plague with them as well. In this too thought, Hallenberg, was lucky, as it was one of the few cities in the area at that time with a fortified stone defense wall surrounding it. Many of the smaller, unprotected villages, such as Züschen, would

temporarily abandon their settlements when raiding or plague was prevalent, and flee to fortified cities such as

Winterberg, Hallenberg, and Medebach, which could seal off their city gates to violence and contagion.

Southeastern Westphalia in 1645. Züschen lies 5 miles downriver of Hallenberg on the Nuhne River

The culmination of the Protestant Reformation took the form of the

Thirty Years War, which began in 1618. It was a particularly violent period for this conflict, and is said to be

one of the most destructive conflicts in all of European history. In 1621, this hostility was brought directly to Hallenberg's doorstep when fighting broke out in the

Landgraviate of Hesse- the territory just south of Hallenberg. In 1623, Hallenberg requested 50 riflemen from Winterberg to help protect the city, which were granted. But by 1632, the city was

plundered for supplies by Protestant Hessian forces none the less, causing its residents to flee for a time. The city was attacked again in both 1633 and 1634, and this second time the

southern fortress gate (the Niedertor, or low gate) of the city was destroyed. No longer having a good way to defend itself, they city suffered much higher casualty rates after this point, and it is estimated that by 1638,

almost half of its original residents had either died or permanently fled. Then, in 1649,

the Swedes, who fought for the Protestant cause, went so far as to set fire to the city in retribution for the

war contributions they felt had not been adequately paid. Certainly many family lines died out completely during this time, and our Wahle line was lucky to not have been one of them.

"The Looting of Wommelgem", 1625-30, by Sebastien Vrancx

Peace finally began to be restored in 1648-49, after the

Peace of Westphalia treaty was signed. Religiously, the treaty attempted to

legalize religious freedom by stating that while a ruler could covert his territory to the religion of his choice, he no longer had the right to force the people to convert with him. Politically, it also established the

modern principle of equal states rights, meaning that no matter how small or militarily weak a nation-state, every independent nation-state had the right of sovereignty over its own internal affairs, without "

might makes right" interference by larger military powers. Although the Holy Roman Empire still existed at this point, its centralized power was now greatly reduced in favor of the widely dispersed kingdoms and electorates.

"The Swearing of the Oath of Ratification of the Treaty of Münster", by Gerard Terborch, 1648, depicting the settlement of one part of the Peace of Westphalia

The records of our Wahle ancestors from this time are mainly found in Roman Catholic church records, albeit only ones after the city fire of 1649. Despite this fire, (and two previous fires in 1400 and 1519), the edifice of the

St. Heribert Catholic Church of Hallenberg has managed to remain relatively unchanged since it was first built in the 12th century. It took a couple generations to fully recover, but from 1708-9 the damage from the Thirty Years War war was repaired, with the

church being rebuilt on its original foundation. In its preserved records, we find the family of Otto Wahle (b. about 1660) and Sybilla Grueseman raising their family of 7 children in Hallenberg during the early 1700's. Many generations of Wahle ancestors were baptized, joined in marriage, and laid to rest within this chapel's grounds.

St. Heribert's Catholic Church, Hallenberg, North-Rhine Westphalia, Germany

Alter of St. Heribert's Catholic Church. The current Baroque alter was probably installed in the 1700s. The previous Renaissance alter is now found in the local Merklinghauser Chapel.

After the Thirty Years War ended, a period a relative peace ensued, which helped to usher in the era of

Enlightenment. As religious and social tolerance became more widely practiced in society, people began to look for truth in science rather than religious dictate. They began to consider their rights as human beings, and how education and intellectual discovery could be put to use for the common good. The implementation of these new ideas was highly variable, however, due to the lack of a strong centralized government and the many fractured independent kingdoms that made up future Germany at that time. Generally speaking, more Protestant areas like the

growing kingdom of Prussia to the northeast, were quicker to put these reforms in place. Meanwhile, strongly Roman Catholic areas, such as Hallenberg, held tight to old customs for longer, and thus were slower to advance.

By 1759, the city no longer contained any noble houses, and most of its less than 200 homes were owned by

small scale subsistence farmers with little wealth.

City Layout of Hallenberg in 1780, consisting of 4 districts: Burg (castle), Raphun, Eisernhut and Eudeut, with the circular town center built around St. Heribert's Catholic Church. The split of the city into four quarters is thought to be due to the relocation of settlers from the nearby abandoned farming communities of Schnellinghausen, Frederinghausen, Gunterdinghausen, Merklinghausen, Wolmerkusen and Beckhausen in the 1500s. Hallenberg today, with the original town layout still seen at its center

Wahle Family Line

Otto Wahle's 3rd child was named

Henrici Wahle (b.1703), and he married Anna Elizabeth Schnurbusch in 1725. Together, they raised 7 children in Hallenburg during the mid-1700s, and were likely farmers like the many generations before. (Only 3 children clearly lived to adulthood, which was

typical for childhood mortality rates in Germany at that time.) Their second born child,

Henrici Jacobi (b.1729), continued the Wahle line when he married Anna Sybilla Möller in 1762 and had another family of 7 children (though two were born stillborn, and another did not live to adulthood.) Many of the

half-timbered buildings, still present in the city today, are thought to have been built at about this time. Their youngest child,

Franciscus Alexander Augustinus Wahle (b.1780), was the child who carried on our line.

As Henrici Jacobi and Anna Sybilla raised their family during the end of the 18th century, things began to heat up again on the world stage. Following the successful American Revolutionary War for Independence, the citizens of France were inspired to undertake a revolution of their own. The

Jacobin party wanted to free themselves from the absolute monarchy of

King Louis XVI and become a secular state. As the world watched on in alarm from 1792-3, revolutionary leaders in France arrested, tried, and then executed (by beheading!) the King. Nine months later, they also beheaded his wife,

Marie Antoinette, who was the sister of Holy Roman Emperor, Joseph II.

In order to help unite the people behind the new government, a politically motivated war was declared on Austrian territory in the Netherlands. After initial military success, in 1793 France expanded its ambitions to territories of Spain, Britain, and the Dutch Republic, with the stated intent of trying to eliminate hostile forces near its borders, and to promote its political ideals throughout Europe. By 1795, with

Napoleon Bonaparte rising in power, it had annexed the Austrian Netherlands and overtaken both the Dutch Republic, and the left bank of the Rhine River, which included parts of Prussia.

"Napoleon Crossing the Alps" by Jacques-Louis David in 1805

Meanwhile, in future Germany, the almost 300 kingdoms/states of the crumbling Holy Roman Empire had been struggling for some time with how to reconsolidate their fading power. Since the end of the Thirty Years War, the

possibility of converting all the remaining

ecclesiastical estates into

secular states had been rumored and schemed, but had not yet come to fruition. However, once France took over the estates west of the Rhine, the rulers of these kingdoms were suddenly more motivated to find a solution that would limit their land/power loses. Newly secular France offered to help "

mediate" the solution to this dilemma, with the understanding that one way or the other, they would be claiming the lands west of the Rhine when it was done. Their proposed solution was to covert all of the ecclesiastical territories into secular states, and then to compensate the secular princes of the west bank with formerly ecclesiastical territories east of the Rhine. As in France, this would result in huge losses of lands for the Roman Catholic Church. The conclusion of these negotiations came to pass on 25 Feb 1803, with

the result being that 112 ecclesiastical states, and over 3 million people, suddenly found their kingdom of origin redefined. Hallenberg, Westphalia was one of these ecclesiastical kingdoms, and that day it transferred hands to the secular state of

Hesse-Darmstadt, who had previously sacked them. They are

said to have imposed a harsh military rule with high taxes that further impoverished the citizens.

1803 reorganization of Holy Roman Empire ecclesiastical estates,

placing Hallenberg within Hesse-Darmstadt

The conversion of all ecclesiastical lands marked the end of the Holy Roman Empire in all but name. Meanwhile, Napoleon continued his French war of conquest, expanding his exploits into Italy, Egypt, and Russia. In exchange for the ecclesiastical lands they had been given, the future German states of Bavaria, Württemberg, and Baden fought in his coalition, while Prussia initially remained neutral. Through 1806, he continued to make military gains. Then Prussia, sick of having France's troops scattered throughout its lands, wreaking havoc as they advanced on Russia,

told the French coalition to get out. When they refused, Prussia joined the war against France as well, and finally Napoleon's army met its equal match. Although it would be several more years of battle, with advances and retreats on both sides, by 1812 Napoleons troops were finally sufficiently reduced to produce a truce with Russia. By 1813, he was suffering heavy losses in Prussia as well, and reading the tea leaves, several of the future German states began to change sides. In 1814,

Allied troops were able to beat the French back across the Rhine River, and eventually took the capitol of Paris. Napoleon finally surrendered on 12 Apr 1814, and was banished to the island of Elbe.

Napoleon under the guard of British troops as he is transferred to the Italian island of Elbe

Long term peace plans for the region then commenced at the

Congress of Vienna. By 1815, it had been decided that Prussia would be the best guard of future French aggressions at the Western border, and as such, it was

granted significant new territories of lands, including Rhineland, Westphalia, and Ruhr. During this land acquisition, the city of Hallenberg was transferred back from Hesse-Darmstadt to Westphalia, which now was a part of Prussia. Before this could occur though, in 1811, the remains of the city wall that had existed since the 1300s, was

demolished by the Hessians. The

German Confederation was also created during this time, but it was not yet a county. Rather it was a collection of 39 German speaking nations, of which Austria served as president, trying to replace the centralized power of the Holy Roman Empire. Such was the political climate into which Franciscus Alexander Augustus Wahle started his family when he married Anna Catharina Gross in 1814, and had yet another Wahle family of 7 children. Four of their children lived to adulthood. The first two children, Maria Anna and Peter Joseph, were actually born out of wedlock in 1812 and 1814 respectively, though it may have been that with all the political reorganizations, things were too crazy for an official ceremony at that time. Their fourth child,

Franz Heinrich Daniel Wahle (b.1819), was our direct ancestor.

Modern remains of the Hallenberg city wall, demolished in 1811

With the war finally at an end, the people of future Germany belatedly entered the early stages of the

Industrial Revolution, a process that had started in Britain more than a half century prior. Depending on local resources and proximity to larger cities and sea ports, some areas benefited from this economic transition much more than others. In Germany especially, initial industrial advances were primarily confined to a few larger cities. Due to its remote, hilly, rural location at the southern edge of the Westphalian

Sauerland, Hallenberg was not one of the areas well positioned to take part in this global economic reorganization. With the exception of a small number of

cloth makers, carpenters, shoemakers and tailors, the majority of its citizens were still small-scale subsistence farmers using old, non-mechanized forms of agriculture. The

cottage industries of these small farming communities were further disadvantaged by the removal of the

Continental Blockade against trade with Britain after the Napoleonic wars. It left them exposed to competition from the much more refined and established goods available in the already industrialized west. Thus, rather than benefiting from industrial progress, many rural areas like Hallenberg went into a protracted state of economic decline.

Frontier Cultural Museum in Staunton, VA,

demonstrating typical 18th century farming in southwestern Germany

As the Industrial Revolution in Germany progressed, people in the cities began to learn new skills, and a

new middle-class of business men, including mine owners, railroad developers, university professors, skilled machine operators and the like, began to emerge. Among this class, the sentiment began to build that it should be education and talent, rather than aristocratic "right of birth", that held the political reigns of power. This liberal ideology spilled over into the working class factory and agricultural workers,

who sought radical improvements in their working and living conditions. By 1848, the German Confederation found itself in the midst of its own Revolution, with riots breaking out in states all across the union. That year in the town of Hallenberg, residents

formed a protective guard in order to defend the city from the unrest of the rural farmers. Despite its strong conservative Catholic roots, most citizens of Hallenberg have tended to be

Centrist in their political views. We do not know whether Franz Heinrich Daniel Wahle was a rural farmer or a city dweller, but this was the world around him as he and Maria Elisabeth Schauerte tied the knot in January of 1849.

Cheering Revolutionaries in Berlin, 19 March 1848, Artist Unknown

Unlike the revolution in France, the revolution in the German Confederation was less well coordinated, and the rulers of the separate states managed to suppress the rebellions by July 1849. Although pressure for the redistribution of political power would continue to strengthen, Germany would stay an

autocratic monarchy until 1918. Many liberal Germans were exiled from the Confederation after this rebellion, and left for America. A large number immigrated to Ohio, where they were known as

Fourty-Eighters. The Wahle family stayed, however, and Franz Heinrich Daniel and Maria Elisabeth raised a family of 10 children. Unlike the Wahle's before him though, Franz Heinrich Daniel Wahle chose to relocate to the nearby village of Züschen, where his wife's family had been established for many generations. At least 7 of their children survived to adulthood and went on to have families of their own. All but two seem to have stayed in Züschen for the long haul.

Village of Züschen in Winterberg, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

In the years following the failed German Revolution, attempts were made by both Austria and Prussia to further consolidate the German Confederation of States. First Prussia, and then Austria, began to exert diplomatic pressure on the smaller states to give up their sovereignty and formally join with them, in exchange for greater unified power. This eventually

set the stage for a possible civil war within the German Confederation, which was coming to a head by the 1860s. Meanwhile, Franz Heinrich Daniel's wife, Maria Elisabeth, gave birth to their 6th and 7th children. Twin boys, born 8 Feb 1861, one name Adam Wahle, and one named

Joseph Wahle. The first would spend the remainder of his life in Germany, the second would one day be bound for America. (See Note 1)

Nation-States of the German Confederation prior to 1866. Hallenberg/Züschen are part of Prussia and nearest to the labeled city of Cologne

The final straw for relations between Austria and Prussia occurred in

June of 1866, when the two rivals got into a tug of war about how administration of the jointly conquered Denmark territories of

Schleswig-Holstein should occur. Prussia felt that Austria was overstepping its bounds, and ordered Austrian troops out of Holstein. When Austria refused, Prussia moved its troops into the Austrian leaning states of Saxony, Hesse, and Hanover. Austria responded in kind. Over the next seven weeks, a series of battles ensued, with victories mostly going to the Prussians. By August, Austria was ready for peace talks. At the

Peace of Prague, the German Confederation was formally dissolved, and Prussia was allowed to annex four of Austria's allied territories: Hanover, Hesse-Kassel, Nassau, and Frankfurt. With Austria no longer in the picture, Prussia was free to form a new military alliance called the

North German Confederation. By 1871, this Confederation had transformed itself into the

German Empire, over which

Wilhelm I was set as the

German Emperor (ie Kaiser).

The German Empire in 1871

If the Wahle legend is to be believed, sometime in about 1885, when he was 24 years of age, Joseph Wahle stole one of the Kaiser's horses, and was forced to flee to America. Given that the Kaiser/Emperor was based in Berlin though, and would have had no reason to go to the back county of Züschen, or to keep his horses there, it is unclear to me how this would have happened. Perhaps he went to Berlin? More likely though, poverty was the reason for his immigration. Child mortality in Germany

between the 1830s-1870s was almost 50%, and the 1880's recorded the greatest number of German immigrants to America ever. They came mainly to

escape the downward economic mobility being endured by rural communities since being left behind by the Industrial Revolution. In fact, by 1900, 1 in every 4 Chicagoan's was either born in Germany, and/or had a parent who was. Moreover, the economic situation in Hallenberg did not improve until after WWII, when

industry and tourism finally began to take root.

Late 19th century ship with German immigrants boarding for America

Joseph Wahle landed in New York City on 5 Sep 1885, on a ship called Elbe. His financial circumstances were such that he had to ride steerage rather than cabin class, which was common for the poor. By 1889 he is living in Chicago, but he may have stopped in Cincinnati, Ohio along the way, as that is where the family of his future wife,

Maria Christina Dietrich was living. Her family had immigrated from Hallenberg two years prior, and likely they knew one another before coming to America. By May of 1888, they had married and started a family of 9 children in Chicago, though sadly their first child died at the age of only 5. They lived in the

Bricktown neighborhood of Chicago, and by 1910, Joseph was an inspector at a structural steel works plant. Their second to last child,

Joseph Gerard Wahle (b.1905) was our direct ancestor. Joseph Wahle died in Feb 1918, at the age of 57, when Joseph Gerard was 12. Seven months later, the Spanish flu of 1918 descended upon the city, and their second oldest child, Harry, died as well. In order to help ends meet, the 2 oldest daughters worked as stenographers, while the next oldest son worked as a mason. Harry, Joseph, and eventually Maria "Mary" Christina were all buried together at

St. Boniface Catholic Cemetery in Chicago, IL. Many other Wahle ancestors are buried here as well.

Grave marker at St. Boniface Cemetery in Chicago, IL for Joseph Wahle, Maria Christina (Dietrich) Wahle, and their son Harry Wahle

Notes

1) Actually, I cannot find any records for the marriage or children of Adam Wahle (b.1861), nor a death certificate that has a different date than his twin brother Joseph's, though there are two different birth records. Possibly Adam actually died at birth? The fact that Joseph is listed as Joseph Adam on his death records though almost makes me wonder if they are really the same person instead? That is only the case for his death records though, so the middle name could have just added by family. Perhaps he took it on as an honorary middle name, in remembrance of his twin brother, at some point later in his life?

%20with%20identical%20twin%20Mary%20Jane.jpg)